By Ol Perkins and James Millington, King’s College London

When you think of fire and climate change, you might think of images from last summer’s fires across Greece or Northern Canada. Rightly so – these represent an important and growing climate adaptation challenge. However, fire also has another important interaction with climate change: by restricting our ability to mitigate it through reforestation (tree planting). Reforestation is one form of land-based carbon dioxide removal – sometimes called ‘offsetting’. A worst-case scenario for fire and carbon removal would see large-areas dedicated to planting new forests, only for them to go up in smoke.

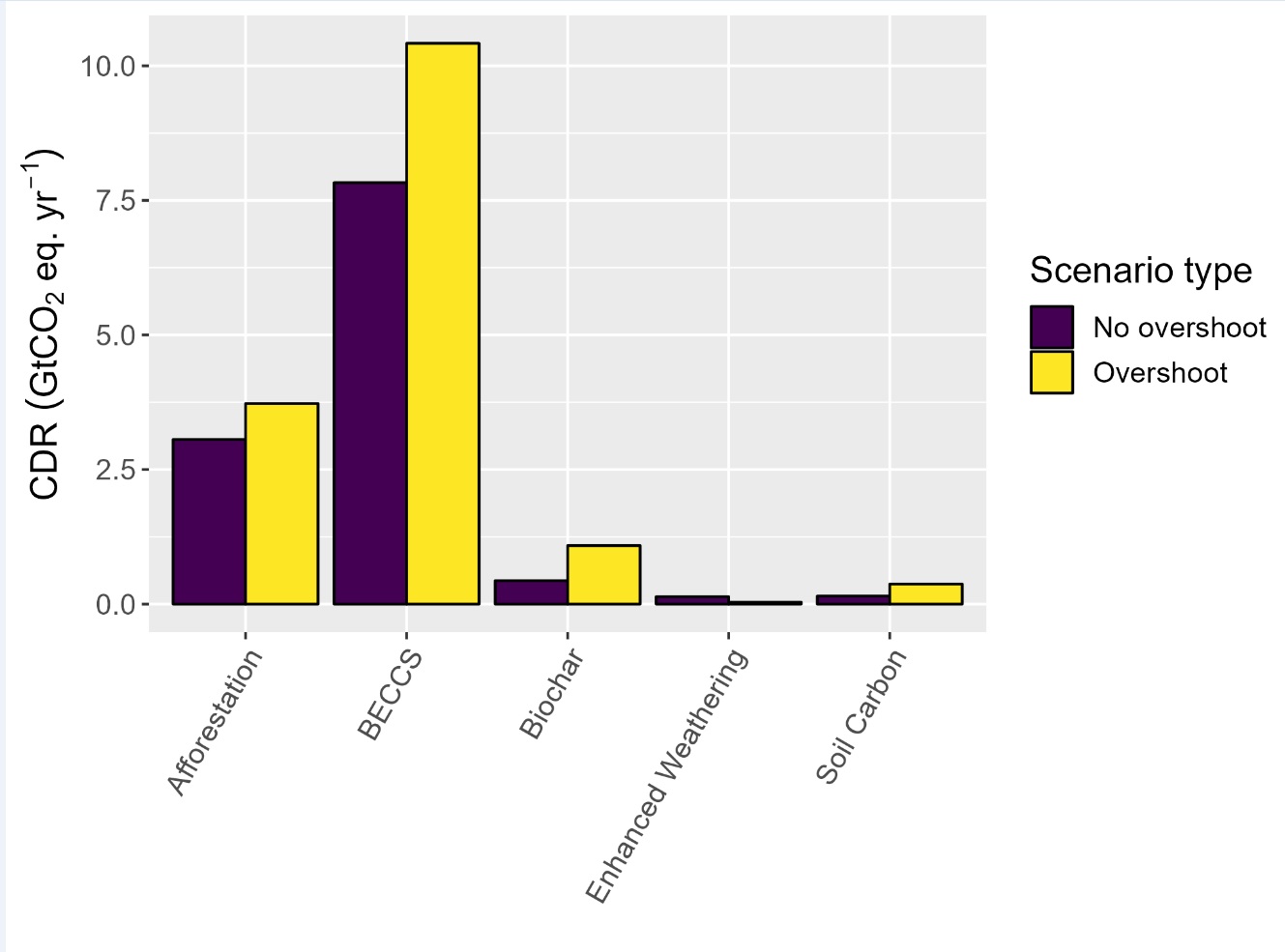

In the lead up to COP28 in the UAE, there was much comment about the role of land-based carbon dioxide removal in countries’ decarbonisation plans. Land-based carbon dioxide removal is controversial for many reasons: not least because countries and companies can use it to justify delayed emissions’ reductions, whilst still claiming compatibility with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Delaying action on climate change on the basis of future carbon removals is obviously risky. If we can’t deliver the planned removals, we will be stuck with higher global temperatures and no safe way to reduce them.

In our recently published paper, we give reasons to be concerned that countries’ plans for land-based carbon dioxide removal are not practical. More positively, we set out ways to define more realistic global targets for offsets as a part of an overall strategy to reduce emissions and limit global temperature rises. This could inform a more policy effective response to climate change.

Our new paper covers a wide range of risks to delivery of carbon removals: from land tenure insecurity to monitoring and evaluation. One important area we describe is in fire risk. We argue modelling fire as a dynamic socio-ecological process – i.e. with both its human and natural parts – can lead to substantial advances in our understanding of fire risk to reforestation. In making this case, we highlight work we have been conducting in the Leverhulme Centre to integrate insights from social science around human fire use and management into global-scale fire models. One example of this is currently in review for publication, featuring authors from Royal Holloway, Imperial College and King’s.

We hope that our work can be one small step towards a robust policy response to climate change.

Ol Perkins is a PhD student at King’s College London, supervised by Dr James Millington. Contact: oliver.perkins@kcl.ac.uk

Feature image: Forest fire in Oregon, by EnviroHope1 from Pixabay