In participatory video research, researchers facilitate a process whereby research participants iteratively plan, shoot, edit and screen videos exploring issues that are important to them. Participatory video can foster dialogue and shared action within communities and open communication between communities and external actors. Yet, as with all participatory research, it must be conducted with mindfulness about the ways in which such processes are shaped by the power relations between researchers and research participants. There is a rich literature exploring the opportunities, challenges, and paradoxes of participatory video research (see references below).

In a workshop in April 2024, we learned experientially about this research methodology by participating in video-making ourselves. This was also an opportunity to reflect, through the themes explored in the videos, on our experiences in the Centre in its first 5 years of existence. We began the day with an open discussion exploring possible themes to develop in videos. The topics we covered included, among others, the extent to which the Centre has fostered interdisciplinarity, the experiences of international students coming to the UK to join the Centre, and the move from digital to in-person interactions after the Covid pandemic.

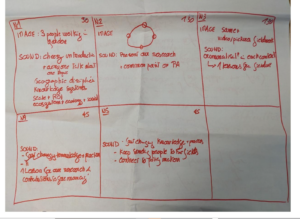

Themes of our discussion

We then split into two groups to plan, shoot, and edit videos, deciding to have one group comprised of PhD students and the other of staff. The staff group explored the theme of communication, thinking about communication to develop research between different disciplines, a shared culture within the Centre, and shared understandings about fire for communication with the media and public. The PhD group used their video to explore their common experience of finding research participants reluctant to discuss fire in contexts where fire use is stigmatised and/or illegal. With a marathon effort, in 3 hours the groups storyboarded, shot, and edited their videos, which are available to watch below.

Storyboard made by the PhD group

We closed the day by screening our videos and reflecting on the video-making process. We discussed how using participatory video in research, especially in the Global South, requires a significant time investment to develop the necessary trust and skills with research participants. Fire can be a sensitive topic, and one that research participants may be reluctant to show or discuss on camera.

Though our experience of participatory video was significantly more condensed, we agreed that producing videos in such a short space of time was a great way to focus our thoughts and discussions. Above all we agreed that we had had fun (!) and we had appreciated the chance to have such open conversations about the past and future of the Leverhulme Centre.

Feature image: Getting stuck into video editing

References:

Kindon, S., 2016. Participatory video as a feminist practice of looking:‘take two!’. Area, 48(4), pp.496-503.

Milne, E.J., 2016. Critiquing participatory video: experiences from around the world. Area, 48(4), pp.401-404.

Milne, E.J., Mitchell, C. and De Lange, N. eds., 2012. Handbook of participatory video. Rowman & Littlefield.

Mistry, J. and Berardi, A., 2012. The challenges and opportunities of participatory video in geographical research: exploring collaboration with indigenous communities in the North Rupununi, Guyana. Area, 44(1), pp.110-116.

Mistry, J., Berardi, A., Haynes, L., Davis, D., Xavier, R. and Andries, J., 2014. The role of social memory in natural resource management: insights from participatory video. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(1), pp.115-127.

Mistry, J., Bignante, E. and Berardi, A., 2016. Why are we doing it? Exploring participant motivations within a participatory video project. Area, 48(4), pp.412-418.

Mistry, J. and Shaw, J., 2021. Evolving social and political dialogue through participatory video processes. Progress in Development Studies, 21(2), pp.196-213.