Photo: Crop residue burning in the Punjab, India (2020). Different waste materials are burnt at different times of year. Unlike here in Feb, in Oct/Nov it is mainly the leftover straw from rice production. Millions of tonnes of material are burned annually. Credit: M. Wooster, King’s College London.

Outdoor air pollution is the world’s greatest environmental health risk (WHO 2016), and the fine particulate matter (PM2.5) component is a leading cause of morbidity and premature death across much of South Asia. In recent years, a series of severe post-monsoon air pollution episodes have engulfed parts of Northern India, leading to state governments enforcing bans on crop residue burning (CRB), which was believed to be a major source. However, at present many farmers have few affordable alternatives for removing residue material, so burning remains widespread. The resulting smoke is transported hundreds of kilmetres along the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP), potentially impacting the quality of the air breathed by hundreds of millions of citizens, including in the capital, Delhi.

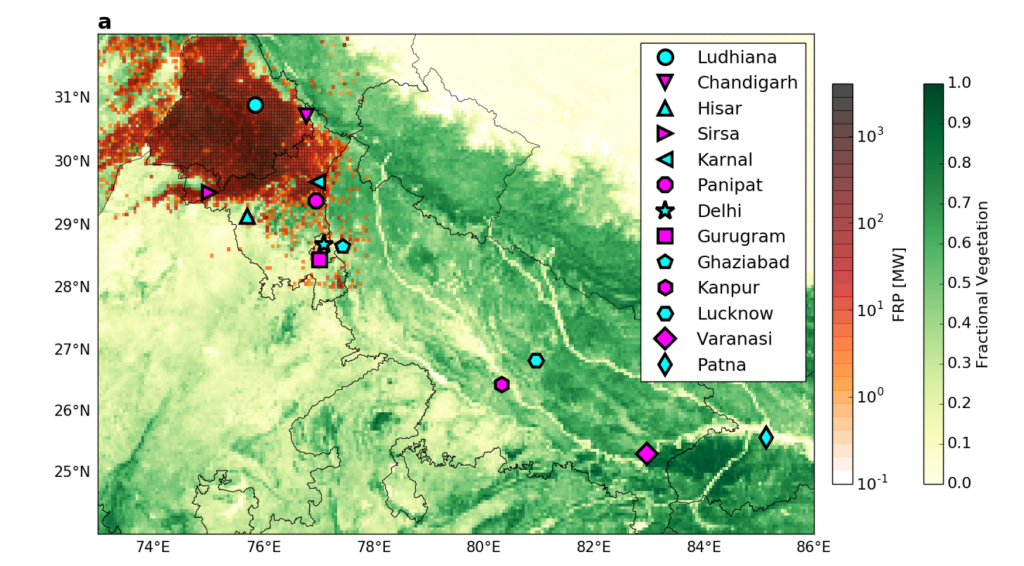

The fires mostly occur in NW India (see Fig. 1) where farmers predominately operate a high yield dual rice-wheat cropping system. Rice residue burning occurs in the winter (Oct-Nov), after the Indian monsoon season. Some studies have suggested that an unintended consequence of an agricultural policy introduced in 2009 to reduce reliance on groundwater for rice production, is to have intensified these air pollution episodes, essentially by making the rice residue fires occur later in the winter season. However, a new study published in Environmental Research Letters has revealed that though changes in the fire timing have occurred, these have been far less important to intensifying these winter air pollution episodes than the increasing amounts of agricultural residue that is being burned.

The research team consists of Dr Harjinder Sembhi and Prof Hartmut Boesch from the University of Leicester and NCEO, Prof Martin Wooster and Dr Tianran Zhang from the Leverhulme Centre for Wildfires, Environment and Society at King’s College London, The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) – a NGO based in Delhi, The Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, Imperial College London, and experts in environmental health and policy from Panjab University (India) and PGIMER (India).

The team found that at the state-level, rice residue burning had indeed shifted later by approximately 10 days since the groundwater preservation policy was implemented in 2009, with the similar change in rice cropping indicating that farmers were adhering to the policy to protect future groundwater reserves. However using new satellite data on rice residue burning from King’s College London, and air quality modelling and emissions inventories from TERI, when the team calculated how PM2.5 concentrations across the IGP changed with and without this CRB timing shift they found it made only a small contribution to the worsening air quality. This was far more dependent on the specifics of the prevailing meteorological conditions and changes in the amount of rice residue burnt, which the satellite data showed had increased substantially since before 2009. The modelling also demonstrated that whilst the groundwater preservation policy introduced in 2009 is helping to successfully address a very important environmental issue, it may be wise to avoid further delays to rice planting until there is a large scale uptake of residue burning alternatives. The findings from the study have implications for improving air quality and health across northern India, and for the National Clean Air Program.

The findings from the study have implications for improving air quality and health across northern India, and for the National Clean Air Program

Dr Sembhi, an Earth Observation scientist who led the study said, “Our modelling showed that reducing the amount of rice residue burnt always reduced PM2.5 concentrations across IGP cities, and far outweighed the influence of the residue burning timing shifts experienced so far in NW India. We also found that if residue burning is not mitigated and instead is just delayed further into the winter, there is the danger that air pollution episodes could be further amplified even if the amount burnt remains the same”.

Prof. Martin Wooster, Associate Director of the Leverhulme Centre for Wildfires, Environment and Society at King’s College London, explained further, “By combining satellite data and air quality models we have been able to disentangle the drivers of the worsening air quality seen across much northern India. Our results confirm that rather than focusing on the exact timing of the fires, it is the Government-led efforts to provide farmers alternative means for residue management that are crucial to improving the air quality and health of Indian citizens.”

Dr Sumit Sharma from TERI added, “This study shows the role that extensive burning of residues plays in deteriorating air quality in the IGP. We recommend developing district level plans for management of residues and converting them into energy or other useful products in states of Punjab and Haryana”.

New policies on crop residue burning will need to safeguard farmer livelihoods and offer affordable and practical alternatives to burning which the farmers will be on board with – “It is critical to support grassroots behavioural change, as it is the farmers themselves who are the first to interact with the harmful emissions of CRB”, said co-author Dr Suman Mor, of Panjab University in India.

Contact: Dr Adriana Ford, Centre Manager, Leverhulme Centre for Wildfires, Environment and Society, wildfire@imperial.ac.uk